SPHERES-an initiative recently announced by the CDC-is a new national genomics consortium that will help public health experts better understand transmission dynamics, host response, and virus evolution

As hospital and health system leaders are dealing with the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on their institutions, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is seeking ways to deal effectively with the next wave. For some hospitals, particularly those in hot spot areas, the virus’s steep climb has reached a plateau or is in decline. For others, the predicted overrun of their system never materialized-and may or may not as America reopens for business.

The CDC recently warned of a worrisome increase in some states, and says a spike in the fall is conceivable. During a daily briefing June 12, Jay Butler, MD, the CDC’s Deputy Director for Infectious Diseases, said, “While what will happen is uncertain, we have to pull all our efforts towards gearing up for additional potential challenges that we see every fall and winter, and that is influenza. If anything, we must be over-prepared for what we might face later this year.”

How should hospitals and health systems respond to future outbreaks? The CDC is counting on this new national genomics consortium, SPHERES, to help.

The precision health and genomics initiative, also known as SARS-CoV-2 Sequencing for Public Health Emergency Response, Epidemiology and Surveillance-(SPHERES) will help coordinate the response to COVID-19 in the US, according to the CDC. It will provide support to public health experts in their efforts to:

- observe the virus as it changes and continues to circulate;

- gain insights during contact tracing;

- identify diagnostic and therapeutic targets; and

- advance research initiatives, particularly in the areas of transmission dynamics, host response, and virus evolution.

The precision health and genomics initiative is not unique to the coronavirus pandemic. Gene sequencing is used to help track seasonal influenza and was implemented during the Ebola outbreak in 2014. But it underscores the importance that genome and precision health are gaining as tools to improve infection detection, tracking, diagnosis, and treatment.

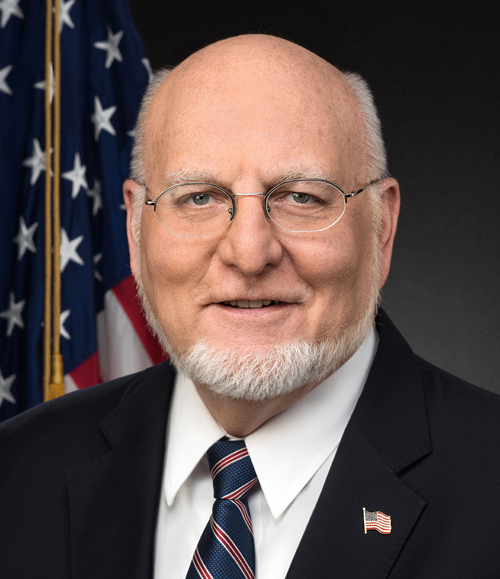

“The US is the world’s leader in advanced rapid genome sequencing,” said CDC Director Robert R. Redfield, MD, in a May 1 news release. This coordinated effort across our public, private, clinical, and academic public health laboratories will play a vital role in understanding the transmission, evolution and treatment of SARS-CoV-2.”

Robert R. Redfield, MD (above), directs the CDC in the launch of SPHERES, a national COVID-19 response initiative allowing public health scientists to monitor changes in the virus as it circulates while providing crucial diagnostic and potential treatment. (Photo credit: CDC.)

The news release also notes that SPHERES aims to “coordinate SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing nationally, organizing dozens of smaller, individual efforts into a single, distributed network of laboratories, institutions and corporations.”

The initiative includes 20 academic institutions, all of which are affiliated with hospitals and health systems, including Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, New York University, and six University of California system. Participating federal agencies include the CDC, Argonne National Laboratory, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Standards and Technology, the National Center for Biotechnology Information, and Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. Twenty state and local public health laboratories, 13 commercial entities, and 10 non-profit health/research institutes are also involved.

Access to Critical COVID-19 Data

The importance of the SPHERES project to hospital and health system leaders was articulated in an article in The New York Times. “Sequences themselves mean little without context,” notes the article. “The consortium aims to standardize what information should accompany each sequence, such as where and when a sample was taken, critically important details to make use of the data.” The group is working on how to circulate information in a coordinated fashion, enabling researchers to access this critical data as they design vaccines and therapies. As some coronavirus hot spots have reached their plateau and others are declining, there is still a lot that public health experts do not know. A consortium such as SPHERES can help advance vaccine and treatment development, giving hospital and health system leaders hope that future waves of COVID-19 can be met with effective preventive, diagnostic, and treatment strategies.

As the CDC notes, “genomic sequence data can give unprecedented insight into the biology of SARS-CoV-2 … and help define the changing landscape of the pandemic.” In fact, such efforts are already paying dividends. In a recent segment on CNN’s AC 360, Chief Medical Correspondent Sanjay Gupta, MD, noted how genome sequencing is beginning to tell stories of how the virus arrived and spread. Some of what is being learned confirms original suspicions. For instance, in New York, it was discovered that the virus came from Europe, whereas on the West Coast it came primarily from Asia.

As for how the virus can change, Gupta explained during the AC 360 segment that “the virus is largely stable, but it [contains] tiny mutations.” These mutations are what form the basis for these so-called stories. For example, “we know the first patient was diagnosed on January 21in Washington [state], but 6 weeks later [through genomic sequencing] we saw a descendant of the virus that infected that first patient infecting other people.”

Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, an immunologist at Yale University School of Medicine, provided another example in a recent interview with Bloomberg News. Noting the potential for some individuals with COVID-19 to experience a cytokine storm-the immune system’s over-response in an effort to fight the virus-Iwasaki said, “If we can understand why some people experience cytokine storms, we can better treat them. We don’t have a rational way of designing therapeutics. We’re just giving the same drugs to people hoping they respond. If we can get down to a molecular level of understanding, we can be a lot more effective.”

These are just a few pieces of a puzzle that public health experts are putting together in a race to prevent or at least minimize a repeat of what hospitals and health systems experienced this spring: Overrun hot spots in some areas, expected waves that never materialized elsewhere. As more pieces of the puzzle fall into place-thanks in part to large-scale rapid genomic sequencing-hospitals and health systems will be in a position to respond with greater precision.

-Dean Celia

Related Information:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CDC Media Telebriefing: Update on COVID-19

Transcript – CDC Media Telebriefing: Update on COVID-19

CDC Launches National Viral Genomics Consortium to Better Map SARS-CoV-2 Transmission

Labs Across U.S. Join Federal Initiative to Study Coronavirus Genome

Akiko Iwasaki, PhD Your Risk of Getting Sick From COVID-19 May Lie in Your Genes